This interview was originally published here in Black Agenda Report.

BAR Book Forum: Jennifer S. Ponce de León’s “Another Aesthetics Is Possible”

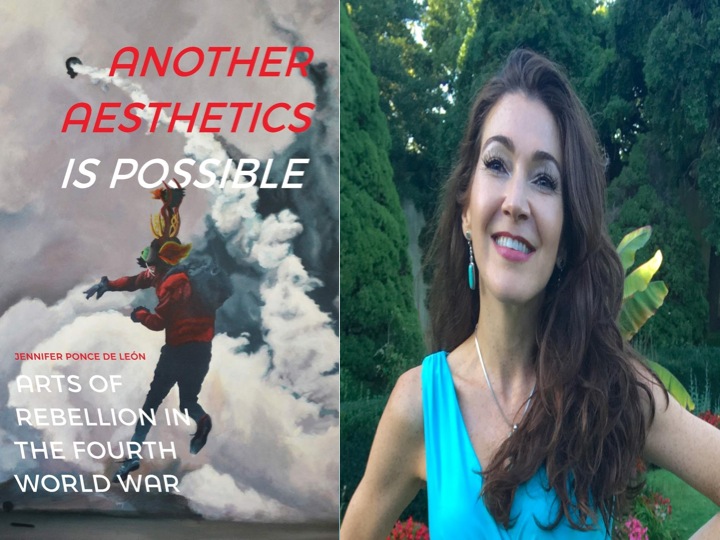

In this series, we ask acclaimed authors to answer five questions about their book. This week’s featured author is Jennifer S. Ponce de León . Ponce de León is Associate Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania. Her book is Another Aesthetics Is Possible: Arts of Rebellion in the Fourth World War.

Roberto Sirvent: How can your book help BAR readers understand the current political and social climate?

Jennifer S. Ponce de León: My book shows how experimental and guerrilla art practices in different parts of the Americas have been influenced by, and have contributed to, recent social movements, uprisings, and popular struggles. These include Zapatismo (the movement constellated around the Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional or EZLN), the human rights movement and 2001 uprising in Argentina, resistance to neoliberal trade policies and U.S. imperialism, and organizing against gentrification in Los Angeles. It demonstrates how these examples of popular politics and cultural action are forms of class struggle insofar as they are developed on the material base of the production and distribution of resources and means that ensure life. It also situates them within a transnational cartography of class struggles since the rise of neoliberalism and globalization in the Americas. It can thereby help readers better understand social conflicts that have emerged in Mexico, Argentina and the U.S and that pertain to state violence, internal colonialism, U.S. imperialism, urban development, immigration, and neoliberal economic restructuring and crises.

To take one example from my book: by analyzing the Argentine human rights movement and activist street art and street theater created within it, I address political tensions within this movement in light of liberal human rights politics’ historical function of legitimating liberal states, condemning counterviolence of the oppressed, and obscuring anti-capitalist strategies. The art by Grupo de Arte Callejero and Etcétera… that I discuss not only addresses the history of state terrorism that has been the principle concern of Argentina’s human rights movement; it also addresses elites’ predatory profiteering and the liberal state’s ongoing repression and co-optation of antisystemic movements. Ultimately, it helps us see the urgency of moving beyond a human rights framework in order to address the routinized destruction and degradation of proletarian lives – what Engels refers to as “social murder.” My analysis brings to the fore the ways in which Argentina’s human rights movement, including the art created within it, has engaged in ideological struggles over how state violence and the history of the Argentina’s most recent Right-wing dictatorship are understood. At stake in this, I argue, is the possibility of understanding how liberalism is a mode of capitalist political management that operates in partial alignment with authoritarianism and fascism, even though liberal ideologies try to convince us otherwise – especially via their framing of violence and fetishization of law.

What do you hope activists and community organizers will take away from reading your book?

By examining struggles that take place within movements and among those who publicly lay claim to particular political projects, my book highlights the necessary work of demarcating those strategies that stand to deliver transformative gains for the working and toiling masses from those that seek minimal reforms that leave property relations unquestioned, as well as from elites’ opportunistic claims to histories and symbols of popular struggle. I hope readers will find useful its Marxist critique of liberal political theater and reformism, its resolute internationalism and anti-colonialism, as well as its analysis of state violence and authoritarianism as rational and predictable forms of class warfare. Such critiques are broadly relevant in our current conjuncture, as capitalists’ profiteering has created unprecedented inequality and ecological catastrophe, and ruling elites take increasingly authoritarian measures to maintain social control in this context, regularly using institutions of bourgeois liberal states to this end.

Another Aesthetics Is Possible discusses an array of creative tactics that have been used in community organizing, protests, and international solidarity, including as forms of popular justice and guerrilla political education. I hope activists and organizers will be interested in these. While some examples I discuss have serious limitations in terms of socialist strategy, we can nonetheless learn from their radical critiques of the contemporary social order, which respond to concrete instances of class struggle and exemplify knowledge collectively produced therein.

Finally, I hope activists and organizers will appreciate my book’s insistence on tracing connections between class struggles that have emerged in different national contexts, as the politics that follow from this should take proletarian internationalism to be foundational.

We know readers will learn a lot from your book, but what do you hope readers will un-learn? In other words, is there a particular ideology you’re hoping todismantle?

I’m hoping to dismantle bourgeois ideologies about art and aesthetics that depict these as autonomous from the material realities and relations that structure the social world. These help to uphold elitist and colonial hierarchies of cultural value; they also obscure the ideological uses ruling classes constantly make of the arts, as well as the social relations that undergird the production, circulation and consumption of culture. Against this, my book theorizes aesthetics as a component of ideology and therefore as a site and weapon of class struggle. This is why, methodologically, it connects the analysis of culture to questions of political economy.

I am also working against bourgeois nationalist ideologies and the way they structure many approaches to studying history and culture. Relatedly, my work rejects identitarian politics and culturalism (the theory that historical development can be explained by cultural phenomena or that cultural features of people transcend changes in economic and political systems). For example, in my book’s chapter on Zapatismo and the art of Fran Ilich, I demarcate the anticolonial anti-capitalist politics of the EZLN (a rebel political force whose base is principally indigenous) from state-aligned forms of multiculturalism (e.g. indigenismo). In this way, I show how culturalist forms of redress can, in fact, shore up the power of elites who actively oppose popular struggles for self-determination, democracy, and land.

Another chapter discusses the guerrilla counter-monuments of the Pocho Research Society of Erased and Invisible History and work by its founder Sandra de la Loza and collaborator Ricardo A. Bracho. I took this as an opportunity to write about Chicana/o/x art practices, which I’ve researched for some 20 years, in a way that does not focus on or fetishize cultural identity. By instead analyzing those social forces that have positioned Mexicans and Chicana/o/xs within racialized and neocolonial class relations and political structures, we can far more effectively understand the conditions that face us and how to act upon them. For example, to understand the displacement of working-class Latina/o/xs and Latin American immigrants to and within L.A., which is the principle subject of the Pocho Research Society’s work, we need to understand the dynamics of profit-driven urban development, the racialized stratification of global labor, U.S. imperialism and militarism in Latin America, the function of borders and citizenship to create hyper-exploitable labor pools, and the consequences of neoliberal development policies for workers.

Who are the intellectual heroes that inspire your work?

I am most inspired by the international tradition of Marxism, so I’d have to start by naming Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Luxemburg. But (as Lenin insisted) Marxism is not just the product of intellectuals; it is the living struggle of the working and toiling masses and the knowledge this produces. When people mischaracterize Marxism as Eurocentric by identifying it as the intellectual product of a few thinkers, they are negating the history of countless people around the world, as well as the work of so many intellectuals outside of Europe. I have been inspired by revolutionary socialists in the Third World who have elucidated dynamics of colonialism, neocolonialism, and imperialism, as well as possibilities for combatting them and creating socialist societies. They include Samir Amin, Frantz Fanon, Che Guevara, Marta Harnecker, Ho Chi Minh, José Carlos Mariátegui, and Walter Rodney. Amilcar Cabral’s theorization of culture as determined by class struggle, including struggles for national liberation, was formative for me. I have learned so much from the work of Antonio Gramsci and Another Aesthetics Is Possible is very much informed by his theorization of the ways class domination is exercised within institutions of civil society. Bertolt Brecht is another intellectual hero of mine, as are Paulo Freire, Eduardo Galeano, George Jackson, and Domenico Losurdo. Augusto Boal’s materialist theory of aesthetics influenced my thinking, as has the praxis of many other artist-intellectuals, including Ricardo A. Bracho, Cine de la Base, Roque Dalton, Patricia Galvão, Grupo Cine Liberación, Yolanda López, and Boots Riley. I have great admiration for the work of Justin Akers Chacón, Mike Davis, Michael Denning, Radhika Desai, Barbara and Karen Fields, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Gabriel Rockhill (with whom I am currently writing a book), Mary Louise Pratt, Adolph Reed Jr., William I. Robinson, María Josefina Saldaña-Portillo, Rosaura Sánchez, and Raúl Zibechi. I am indebted to their work, as well as to that of many others I cannot name here. I am also profoundly inspired by the intellectual production of the EZLN — for the modalities of political communication they have created as well as for their astute analyses of contemporary class warfare.

In what way does your book help us imagine new worlds?

It can help us imagine how the arts can actively contribute to movements seeking emancipation from exploitation and oppression, and also envisage how the arts, including institutions that organize their production and circulation, could be transformed in this process. The art and literature I analyze in Another Aesthetics Is Possible evinces an omnivorous experimentalism that is directly related to the artists’ efforts to contribute to Left movements and effectively communicate and collaborate with working-class people while avoiding the gatekeeping and rarefication of the arts that is performed by elite cultural institutions. They not only experiment with and combine recognized artistic forms; they also take up techniques and forms from practices considered extraneous to the arts, while creating alternative means of producing and circulating art that alters the social relations this typically involves. For example, Grupo de Arte Callejero and Etcétera… combine artistic production with direct-action tactics, while finding audiences and collaborators not in art institutions, but in contexts of organizing and protest. Fran Ilich integrates solidarity markets into his art practice so that it materially supports Zapatista coffee cooperatives. This type of experimentalism has a political logic radically different from the fetishization of marketable novelty that characterizes the culture industries. Instead, it stems from an effort to make art that is useful to our struggles and the recognition that, to do this, this art must be as dynamic as the social reality we inhabit and seek to affect.

The bourgeois press regularly represents popular struggles as local, isolated, and temporary interruptions of business-as-usual; footnotes to liberal progress narratives whose protagonists are elites; or as fruitless utopian gestures. Against this, my book demonstrates that popular struggles that may seem unrelated are, in fact, expressions of global class struggles, which are mediated by the concrete sociohistorical conditions in which they have developed. It thereby helps us to see how the subordinated classes are actively creating another possible world, and that this collective labor is as constant and omnipresent as it is varied in the forms it takes.

Roberto Sirvent is editor of the Black Agenda Report Book Forum.